W.H. Younce lived in Ashe County, North Carolina. At the age of 20 he was drafted into the Confederate Army (which is why he refers to himself as a “conscript.”) In his autobiography, he writes that he was against slavery and therefore did not wish to fight for the confederacy. After he joined the Confederate Army, he quickly deserted and returned to Ashe county. He was captured by the Home Guard and returned to the front lines.

In 1863 he deserted a second time, and this excerpt from his autobiography, written in 1901, describes what he found when he returned home. Because deserters (both Union and Confederate) were sometimes executed, Younce had to find a place to hide, and so he left Ashe County and moved to the hills of Tennessee.

Historians question some parts of this book, such as Younce’s claims of having strong anti-slavery views. Many Southerners wished to remain part of the United States regardless of their views on slavery. Younce also wrote dialogue in his book, and it would have been impossible for him to remember conversations in such detail nearly forty years later. But the events and experiences he described in battle and on the home front match other historical records. His experience was reflective of the danger men faced when they deserted the army or refused to support the Confederate cause.

At Home Again

Our purpose was to try to reach my father’s home that night, but about the middle of the night we had given out with fatigue and hunger, and could go no further. We stopped at a cabin with people whom I knew, and lay down on the floor and slept till nearly daylight, and then started for home. We arrived at my father’s home about eight o’clock in the morning, on Friday, the third day of March, having been on the road just three weeks to a day.

The boys who were with me went to their homes in another part of the Country, and thus ended my second desertion.

I will not attempt to describe the condition of things that existed there at that time. My vocabulary is too limited to attempt a portrayal of the horrors and the sufferings of those poor Union people. Civil law and courts of justice had been abolished, monarchy and ruin reigned supreme; men and neighbors, who had always passed for good men, who had turned to be rebels, were transformed into demons, murderers and savages. Conscripts were hunted like wild animals, and often shot and murdered. Their homes were often destroyed by the torch, and if spared were robbed of everything they had, and their families left without a crust of bread.

The fact that I had deserted the second time was known by the authorities at home before I arrived. My Captain had instructed the Colonel of the Home Guard, as they called themselves, not to return me again to his company, in fact, not to arrest me, but shoot me on sight, and they were on the lookout for me before I arrived. I was informed of these facts as soon as I got home. I then doubled my vigilance, for I well know with me then it was simply a matter of life or death. I decided to find a hiding-pace and allow no one to see me, and at night I would slip in and get something to eat. Every two or three nights five or six of them would come and search house from cellar to garret. But I was very careful not to be there. This was a hard life, and I soon began to grow tired, and at night, as I would like in my hiding-place in the gloomy forest, I would wonder if there were not some way out of this kind of existence, when just at this time a circumstance occurred in the neighborhood that changed the whole course of things, and opened again new fields for adventure.

There lived not far away an old man by the name of Price. He had four or five sons who were conscripts, but up to this time had never been captured. The old man had also gained the amenity of these bandits or Home Guards, and they were seeking to capture him. They had camped on his place during a part of the Winter, and robbed him of everything he had. His family had left their home and sought refuge elsewhere. He had an old mill on a mountain stream near his house, and he and his sons would slip in from the mountains and grind corn for bread, and take it back with them to their hiding-place.

Union Men Murdered

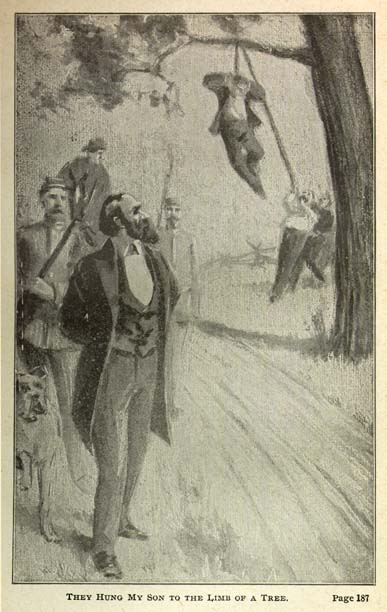

The Home Guards learning they were making frequent visits to the mill, concealed themselves near by and waited for their coming. Price, thinking the way was clear, with two of his sons and a nephew, came to the mill. They were surrounded, taken by surprise, and all of them captured and taken at once to the County-seat and locked up. The next morning, a mob led by Major Long … went to the jail, took these prisoners to a wood near the town, and hanged every one of them. They would tie one of the poor fellows hands behind him, put a rope around his neck, place him on a horse behind one of the mob, who would ride under the limb of the tree, throw the end of the rope to a man on the limb, who would tie it, and then on the horse would ride out from under him, leaving him dangling in mid-air.

The three boys were hung first, one at a time, as I have described. In the crowd that went out to witness the hanging was Dr. Wagg, a prominent physician, and also a Methodist preacher, a man well and favorably known throughout all the country, and be it to his credit, was trying to quell the mob and save the lives of these men. After the three young men had been hanged, Dr. Wagg approached the old man, whom he had known for many years, and told him he could do nothing for him: that he had no influence with these men, and they were going to hang him. "And now," he said "you are unprepared, and in a few minutes more your soul will be ushered into eternity. I am here to try to do you good. Shall I not stay the hand of death, while I pray with you?"

The old man replied:

“Doctor, I have done nothing to be hung for. I am old -- not even subject to military duty. I have committed no crime. I have only been loyal to my country, and if it is for this you intend to murder me, I will go into eternity as I am. I want no rebel, such as you are to pray for me."

In a moment his hands were pinioned, and he was swinging beside the three boys.

When they were taken down, Dr. Wagg discovered that one of the young men was not yet dead, and after some time spent in working with him, he was resuscitated. He was taken back to jail, and as soon as he was fully recovered was sent to the front at Richmond.

He at once made his escape, got to the Union army, and enlisted in the Federal service, and fought throughout the war.

In The Mountains of Tennessee

This happened about two weeks after my arrival home, and convinced me that it was exceedingly hazardous for me to remain in that part of the country. After due consideration we decided that I should go to Tennessee. I had many friends and acquaintance over among the Union people, and would be much safer; besides, if I should be so unfortunate as to be captured I perhaps would not be assassinated, but have a chance for my life. With this understanding I completed my arrangements to go...

Source Citation:

Younce, W. H. The Adventures of a Conscript. Cincinnati: The Editor Publishing Company, 1901. https://archive.org/details/adventuresofcons00youn/page/59.