In 1920, radio broadcasting was in its infancy. Fewer than twenty commercially licensed stations existed across the United States, and fewer than eight percent of American homes had radios. But the radio craze took off quickly, with nearly five hundred stations broadcasting by 1923.1 WBT Charlotte, North Carolina’s first commercial radio station, got in just ahead of the 1923 flood when it acquired its license in 1922.

The station began with just a few hours of programming a day but grew to become a powerhouse of radio in the American Southeast, launching the careers of a number of prominent stringband and gospel music artists. WBT Charlotte rode the wave of the "Golden Age of Radio" until the rise of televised entertainment in the late 1950s.

Early radio: An amateur free-for-all

In the early days of the twentieth century, radio transmission was an exciting and relatively new technology. While radio waves had been used since the late nineteenth century for communications, audio broadcasting for entertainment was an exciting new prospect. Amateurs all over the world experimented with constructing and operating radio transmitters and receivers with varying degrees of success. Before 1912, no U.S. government regulation existed for this young medium, and the result was a free-for-all on the airwaves, with radio novices vying to transmit their voices over short distances.2

American radio fanatics were reined in by the 1912 “Act to Regulate Radio Communication,” which restricted amateurs to transmitting within two hundred meters, purportedly to avoid interfering with military communications. Radio experimentation was forced to a halt entirely in 1917 when the U.S. entered World War I and officials feared the unrestricted transmission of information over the airwaves.3

The birth of WBT

The wartime restrictions were lifted in 1919, and a renewed interested in amateur radio swept the country. Fred Laxton, Earle Gluck, and Fred Bunker, three radio aficionados, met in an amateur radio supply store in Charlotte. The men decided to set up a station, which began operating in 1920. The transmitting equipment was housed in Laxton’s house and the radio receiver was in an old chicken coop in the backyard.4

In 1922, Laxton, Gluck, and Bunker received a commercial license for their radio operation from the U.S. Department of Commerce. The station took on the call letters WBT and became the first commercial radio station in North Carolina -- and in the southeastern United States. WBT’s broadcasting in 1922 consisted of just two hours in the morning and two in the evening, but by this time the studio and transmitter had moved from its humble surroundings to a larger building in Charlotte. The station changed hands two more times over the next few years and was bought by CBS in 1929. In the nine years since its beginning, WBT’s power had increased exponentially, from 100 watts to 25,000 watts.5

Crazy Water Crystals and hillbilly music: The early days of WBT programming

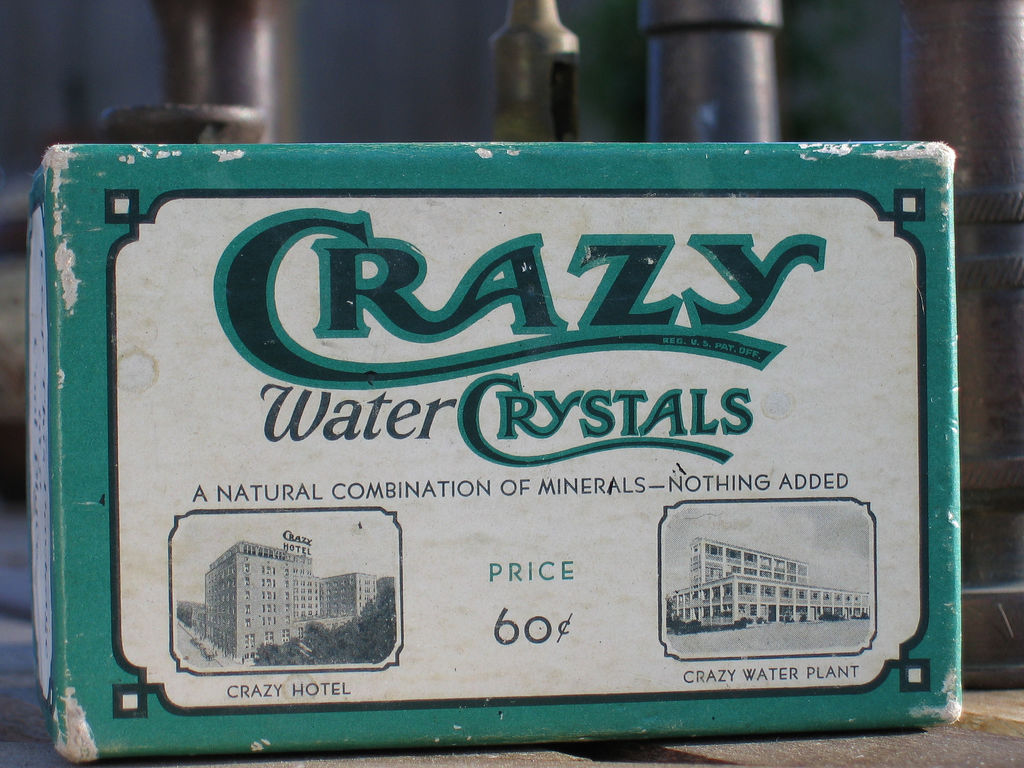

One of WBT's most prominent sponsors in the 1930s was Crazy Water Crystals, a product from Texas that gave the "Crazy Water Crystals Saturday Night Jamboree" radio program its name.

Crazy Water Crystals commercial. Early radio programming was very different from the music-dominated format we associate with modern radio, in which disc jockeys play recorded songs, talk a bit and play a few commercials. In fact, commercial radio programming in the 1920s was just taking shape. In 1928, the staff at WBT included a woman known on the air as "Aunt Sally" who read stories for children, and various music ensembles that played live on the air. A six-piece orchestra, Jimmie Purcell and his Dixonians, played dinner music at the Hotel Charlotte and the performance was broadcast remotely from 12:20 to 2:00 p.m. At 2:00, 100 commercials were read on the air -- one right after the other! On Sundays WBT departed from its weekday schedule and broadcast live from First Baptist Church in Charlotte.6

Beginning in the 1930s, the programming formats that would dominate the "Golden Age of Radio" began to take shape. Before the advent of television, radio programs included dramas, adventure stories like the Lone Ranger, and soap operas. Many were thinly veiled commercials for their corporate sponsors.

One of the most popular program genres was the radio barn dance, which featured live old-time or "hillbilly" music. Part of the hillbilly craze the swept the country in the 1930s, radio barn dances got their start in 1924 at WLS in Chicago and reached the height of their fame with the Grand Ole Opry on WSM in Nashville.7 In 1933, WBT brought its own barn dance program to the scene with the "Crazy Water Crystals Saturday Night Jamboree." The program featured local musicians and promoted Crazy Water Crystals, a product from Texas that was sold as a cure for a variety of diseases. As the Crazy Water Crystals show grew in popularity, its sponsor increased its distribution, and the show was heard from fourteen different stations in three states.8

Briarhoppers and Mountaineers

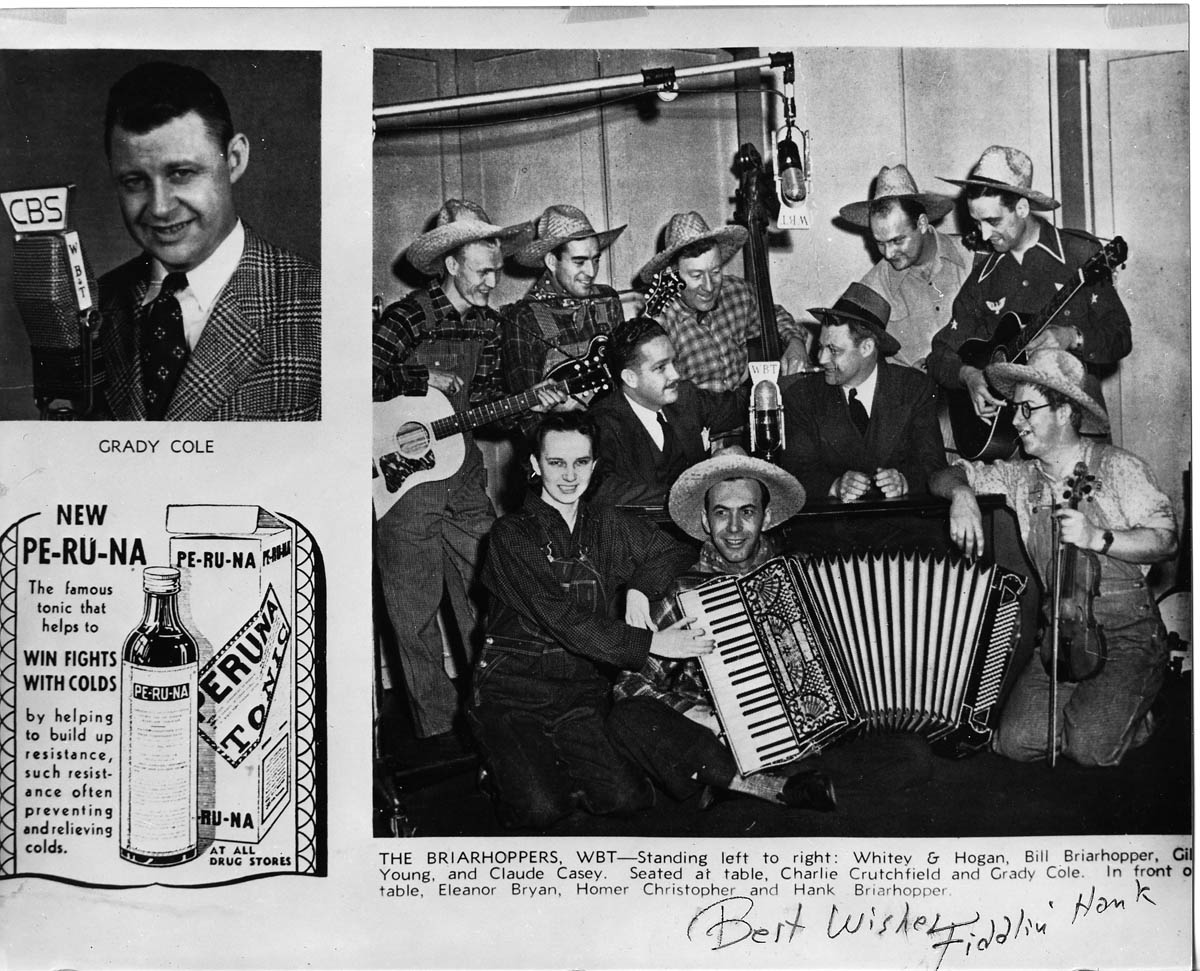

Because of its prominence in the national radio scene, the presence of WBT in Charlotte also presented opportunities for locals who sought a living outside the textile mills. One of WBT’s signature hillbilly acts, the Briarhoppers, started when its two founding members met at a Firestone textile mill in Gastonia.9 They started a group that played locally at a smaller radio station in Gastonia. The audience response went through the roof, and the Briarhoppers were hired at WBT in 1934.10

In this 1930s photo of the Briarhoppers, the straw hats, plaid shirts, handkerchiefs, and overalls show a conscious conformity to the hillbilly stereotype.

The Briarhoppers were featured on the weekday program "Briarhopper Time," hosted by WBT announcer Charles Crutchfield. Whitey Grant and Arvil Hogan, the former mill workers, soon found their wages much higher than they had at the mill. In fact, part of the broad appeal of the Briarhoppers to their radio audience lay in their shared roots. Many of the workers in North Carolina mill towns had moved there from the Appalachian Mountains in search of jobs.11 They listened to the "hillbilly" music on WBT because it was familiar to them. "Briarhopper Time" became "an early showcase for the music then leaving the farms and entering the mill towns and big cities with the migrations of its singers, fiddlers, and pickers."12

Radio stations, for their part, relied on audience response to shape their programming in an effort to build a large listening base, and write-in requests played a large role in determining how broadcast time would be filled. Audience demand for stringband and hillbilly music was reflected in the amount of airtime devoted to programs like "Briarhopper Time" and the "Crazy Water Crystals Sunday Night Jamboree," as well as to other North Carolina hillbilly bands. The Briarhoppers were one of many local string bands who launched their careers on WBT, including Mainer’s Mountaineers, founded by brothers J.E. and Wade Mainer, who had worked in cotton mills in Concord; the Tobacco Tags, who, like the Briarhoppers, were from Gastonia; and Rockingham’s Dixon Brothers.<13

1940s programming

WBT maintained its place as one of the Southeast’s most important radio stations when the Carter Family came on board in 1941. The band, which then consisted of A.P. Carter, his wife Sara, his sister-in-law Maybelle, and Maybelle’s daughter June, is still regarded as one of the most influential country groups in history. The Carter Family played live every morning from 5:15 to 6:15 a.m., on a show sponsored by Peruna Tonic and Kolorbak hair dye.14

In 1944, WBT became the first station in the Southeast to broadcast twenty-four hours a day. Hillbilly music continued to dominate the station, as Arthur "Guitar Boogie" Smith and his Crackerjacks joined WBT. Smith is one of the station’s most well-known veterans, having penned the songs "Guitar Boogie" and "Dueling Banjos."15 Smith had started his musical career in a jazz band, about which he later said:

We nearly starved to death until one day we changed our style... One Friday we threw down our trumpet, clarinet, and trombone and picked up the fiddle, accordion, and guitar. The next Monday we came back on the radio program as Arthur Smith and the Carolina Crackerjacks.

16

But while WBT was still beholden to its stringband-loving audience, the station featured other musical genres as well -- most notably gospel. Among these were the Golden Gate Quartet and the Southland Jubliee Singers. The Golden Gate Quartet played on WBT for over two decades, from 1934 until the 1950s. The Southland Jubilee Singers, who would later become the Four Knights, joined WBT in 1942, appearing regularly on the popular program "Carolina Hayride." The group would later move to New York and record for Decca and Capitol Records.17

By the late 1940s, radio had become the dominant media format in the United States, and most homes had more than one set.18 In a fairly short amount of time, broadcast radio had transformed the way rural and urban culture interacted and the way the American public received information. It wouldn’t be long before, in 1949, WBT would launch WBTV, its affiliate television station. Within the next decade, television would become king and the "Golden Age of Radio" would be over.

- 1. Bensman, M. R. The History of Broadcasting, 1920-1960 Retrieved 17 March 2009 from The Bensman Radio Project Archive.

- 2. White, T. H. United States Early Radio History: Pioneering Amateurs (1900-1917) Accessed 17 March 2009 from United States Early Radio History.

- 3. White, T. H.

- 4. "The History of WBT: The 1920s" Accessed 17 March 2009 from News-Talk 1110 WBT.

- 5. The History of WBT: The 1920s.

- 6. Ibid

- 7. Danaher, W. F. and Roscigno, V. J. (2004). "Cultural Production, Media, and Meaning: Hillbilly Music and the Southern Textile Mills." Poetics, 32(1). p. 65.

- 8. Rosenberg, N. V. (2005) Bluegrass: A History. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press. p. 32.

- 9. "Photos: Pickers and Singers" Accessed 17 March 2009 from BT Memories.

- 10. Danaher & Roscigno, p. 67.

- 11. Danaher & Roscigno, p. 62-64.

- 12. Minehart, T. (1985, Nov. 19). "Country's Capital Could Have Been Charlotte." The Chicago Tribune.

- 13. Carlin, B. & Terrill, S. (2004). String Bands in the North Carolina Piedmont. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 177.

- 14. Russell, Tony. (2003). Country Music Originals: The Legends and the Lost. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 67.

- 15. "The History of WBT: The 1940s" Accessed 17 March 2009 from News-Talk 1110 WBT.

- 16. Carlin & Terrill, p. 179.

- 17. Dunn, Jim. "The Four Knights Biography." Accessed 17 March 2009 from Allmusic.com.

- 18. Bensman.