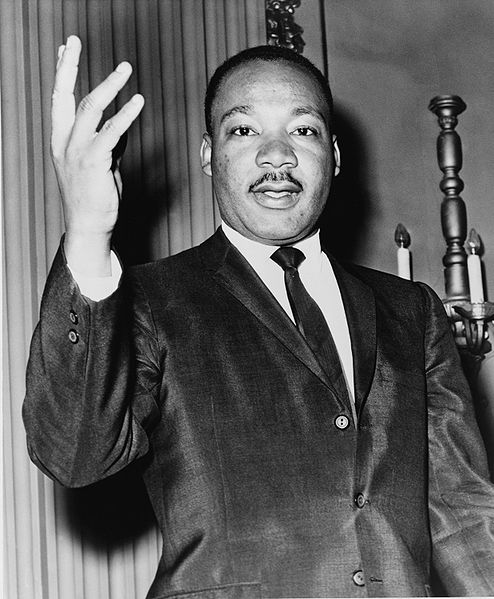

Shortly after the successful conclusion of the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King and a number of senior movement figures — the Reverends Ralph Abernathy, T.J. Jemison, Joseph Lowery, Fred Shuttlesworth, and C.K. Steele, and the activists Ella Baker and Bayard Rustin — founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). This new civil rights organization was devoted to a more aggressive approach than that of the legally oriented NAACP. The SCLC launched “Crusade for Citizenship,” a voter registration effort.

Younger activists, meanwhile, were growing impatient with King’s gradualist tactics. In 1960, some 200 of them, including Howard University student Stokely Carmichael, formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. And in Greensboro, North Carolina, four freshmen at the all-black North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College took matters into their own hands.

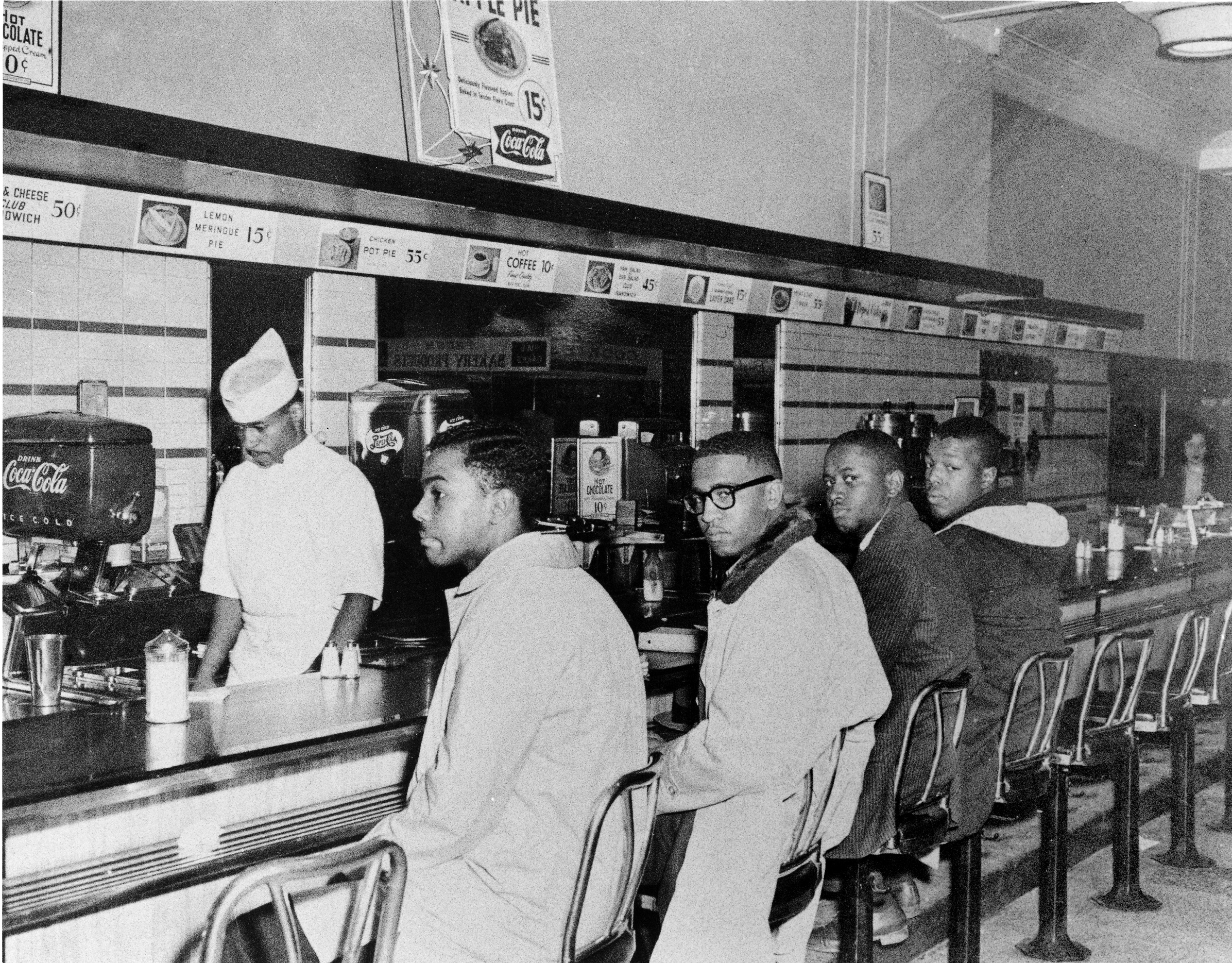

At 4:30 p.m. on February 1, 1960, students Ezell Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin Eugene McCain, Joseph Alfred McNeil, and David Leinail took whites-only seats at a local Woolworth department store lunch counter. They were denied service, but sat quietly until the store closed an hour later. The next morning, 20 Negro students took lunch-counter seats in groups of three or four. “There was no disturbance,” the Greensboro Record reported, “and there appeared to be no conversation except among the groups. Some students pulled out books and appeared to be studying.” Blair told the newspaper that Negro adults “have been complacent and fearful.… It is time for someone to wake up and change the situation… and we decided to start here."

The nonviolent occupation of a public space, or sit-in, dated at least to Mahatma Gandhi’s campaigns for Indian independence from Britain. In the United States, labor organizations and the northern-based Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had employed sit-ins as well. As events in Greensboro began to draw attention, SNCC moved swiftly to associate itself with this civil rights tactic, and over the next two months, sit-ins spread to more than 50 cities.

Particularly significant were events in Nashville, Tennessee, where the King-affiliated Nashville Christian Leadership Council had been preparing for this moment. Back in 1955, King had reached out to the Reverend James Lawson, a civil rights activist and missionary who had served in India and studied Gandhian satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance. King urged Lawson to relocate to the South: “Come now,” King said. “We don’t have anyone like you down there."

Working with King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Lawson in 1958 began to train a new generation of nonviolent activists. His students included Diane Nash, James Bevel, and John Lewis, today a U.S. representative from Georgia. All soon would assume prominence in the civil rights movement. At these training seminars, they agreed to stage a series of sit-ins at department store restaurants. Blacks were permitted to spend money in those stores, but not to eat at their restaurants.

The Nashville activists organized carefully and moved deliberately. But when the Greensboro sit-in began to draw national attention, they were ready. In February 1960, hundreds of their activists began the sit-ins. Their student-drafted instruction sheets captured the personal discipline and dignified commitment to nonviolence they would offer the world:

- Don’t strike back or curse back if abused.

- Don’t block entrances to the stores and aisles.

- Show yourself friendly and courteous at all times.

- Sit straight and always face the counter.

- Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and Martin Luther King.

- Remember love and nonviolence, may God bless each of you.

Typically a lunch counter would close when a sit-in began, but after the first few incidents, police began to arrest protesters, and the subsequent trials drew large crowds. When convicted of disorderly conduct, the activists chose to serve jail time rather than pay a fine.

Nashville was an early example of how Jim Crow could not survive exposure. The legendary journalist David Halberstam was just beginning his career, and his reports for the Nashville Tennessean helped attract national media attention. The sit-in movement spread throughout much of the country, and soon Americans across the nation were stunned by photographs like the one that appeared in the February 28, 1960 New York Times. The caption read: "A white man swings an 18-inch-long [46-centimeter-long] bat at a Negro woman in Montgomery. She was injured by the blow. The attack occurred yesterday after the woman brushed against another white man. Police, standing near by, made no arrest.” On April 19 of that year, a bomb exploded at the home of the Nashville students’ chief legal counsel. Some 2,000 African Americans swiftly organized a march to the City Hall, where they confronted the mayor. Would he, Diane Nash asked, favor ending lunch-counter segregation? Yes, came the reply, but, "I can’t tell a man how to run his business. He has got rights too."

This “right” to discriminate lay at the heart of the struggle. Meanwhile, the bad publicity stung the businessmen of Nashville, as did the stark contrast between the dignified, nonviolent black students and their armed and all-too-violent opponents. Secret negotiations began, and on May 10, 1960, quietly and without fanfare, a number of downtown lunch counters began serving black customers. There were no further incidents, and soon thereafter Nashville became the first southern city successfully to begin desegregating its public facilities.