U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill were responsible for leading their nations to victory and jointly planned strategies for the cooperation and eventual success of the Allied armed forces. Roosevelt and Churchill had already agreed early in the war that Germany must be stopped first if success was to be attained in the Pacific. They were repeatedly urged by Stalin to open a "second front" that would alleviate the enormous pressure that Germany's military was exerting on Russia. Large amounts of Soviet territory had been seized by the Germans, and the Soviet population had suffered terrible casualties from the relentless drive towards Moscow. Roosevelt and Churchill promised to invade Europe, but they could not deliver on their promise until many hurdles were overcome.

Allied soldiers loading equipment for the D-Day invasion, June 1944

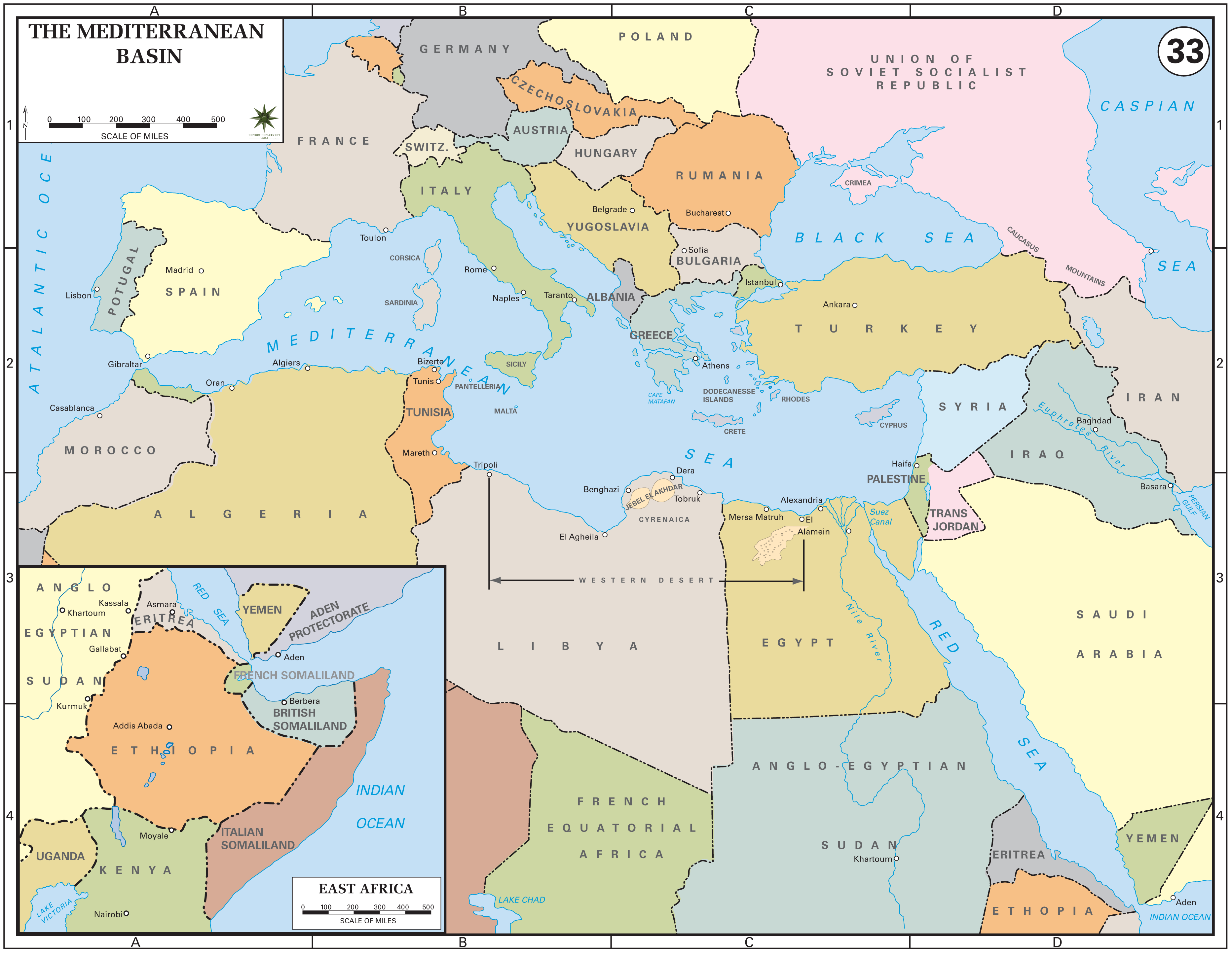

Initially, the United States had far too few soldiers in England for the Allies to mount a successful cross-channel operation. Additionally, invading Europe from more than one point would make it harder for Hitler to resupply and reinforce his divisions. In July 1942 Churchill and Roosevelt decided on the goal of occupying North Africa as a springboard to a European invasion from the south. In November American and British forces under the command of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower landed at three ports in French Morocco and Algeria. This surprise seizure of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers came less than a week after the decisive British victory at El Alamein. The stage was set for the expulsion of the Germans from Tunisia in May 1943, the Allied invasion of Sicily and Italy later that summer, and the main assault on France the following year.

By occupying North Africa, the Allies could use Tunisia as a launching point for an invasion of Italy.

Because of this success, Eisenhower was named commander of all Allied forces in Europe in 1943. When in February 1944 he was ordered to invade the continent, planning for "Operation Overlord" had been under way for about a year. Hundreds of thousands of troops from the United States, Great Britain, France, Canada, and other nations were assembled in southern England and intensively trained for the complicated amphibious action against Normandy. In addition to the troops, supplies, ships, and planes were also gathered. Countless details about weather, topography, and the German forces in France had to be learned before Overlord could be launched in 1944.

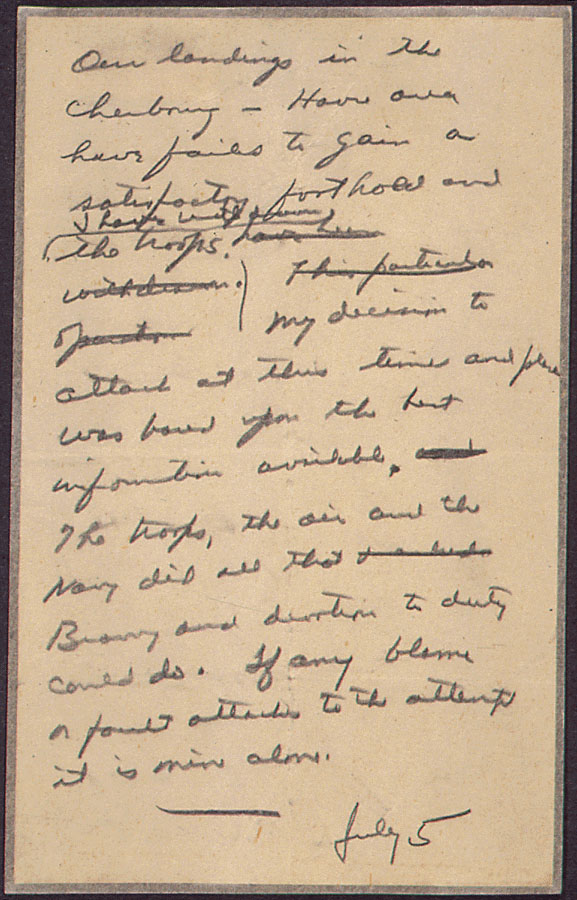

General Eisenhower drafted this note to be sent in case the invasion failed.

General Eisenhower drafted this note to be sent in case the invasion failed.

General Eisenhower's experience and the Allied troops' preparations were finally put to the test on the morning of June 6, 1944. An invasion force of 4,000 ships, 11,000 planes, and nearly three million soldiers, marines, airmen, and sailors was assembled in England for the assault. Eisenhower's doubts about success in the face of a highly-defended and well-prepared enemy led him to consider what would happen if the invasion of Normandy failed. If the Allies did not secure a strong foothold on D-Day, they would be ordered into a full retreat, and he would be forced to make public the message he drafted for such an occasion.

Listen to General Dwight Eisenhower's message to Allied troops before the invasion.

As the attack began, Allied troops did confront formidable obstacles. Germany had thousands of soldiers dug into bunkers, defended by artillery, mines, tangled barbed wire, machine guns, and other hazards to prevent landing craft from coming ashore. The photograph at the top of the page shows some of the ferocity of the attack they faced. About 4,900 U.S. troops were killed on D-Day, but by the end of the day 155,000 Allied troops were ashore and in control of 80 square miles of the French coast. Eisenhower's letter was not needed, because D-Day was a success, opening Europe to the Allies and a German surrender less than a year later.

In this radio broadcast from the beaches of Normandy two days after the invasion, the reporter describes the sounds, smells, and sensations of the battlefield.