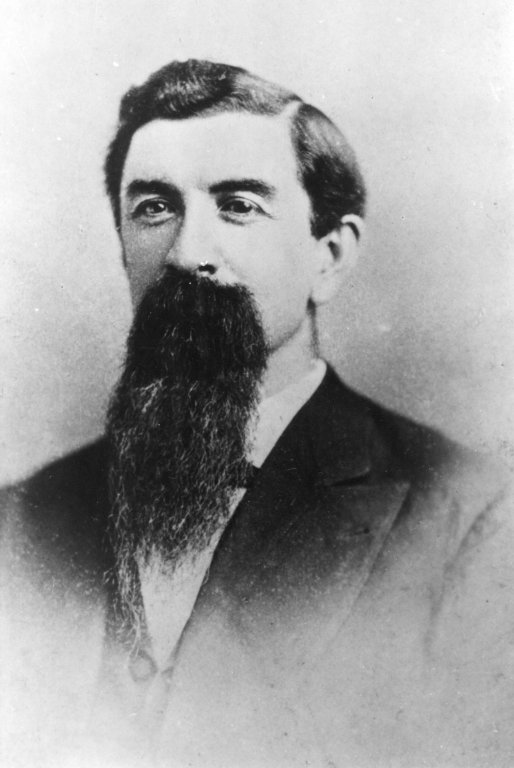

Leonidas Lafayette Polk was born in Anson County in 1837. Prior to the Civil War, Polk owned a modest farm and a number of slaves. Although he was a Unionist, he eventually supported the Confederacy and served from 1862 until he was elected to the state legislature in 1864.

After the war, the North Carolina Central Railroad laid down track near his farm. Polk decided to regain his wealth by selling sections of his property to people who wanted to settle near the railroad, founding a town which he called Polkton.

In 1874, Polk began publishing his first newspaper, the weekly Ansonian. Polk used his newspaper to give advice to farmers, arguing that they should diversify their farms (plant a variety of crops rather than just one cash crop) and raise crops and animals they could use rather than focusing on cash crops such as cotton. In 1877, Zebulon Vance again became governor, and he appointed Polk the first commissioner of North Carolina’s new Department of Agriculture.

Polk resigned from the Department of Agriculture after only three years, unhappy with the lack of support he received from the legislature. In 1886, he founded the Progressive Farmermagazine and used it to advocate improvements in agriculture, farmers’ organizations, and the establishment of a state agricultural college — the North Carolina College of Agricultural and Mechanic Arts, later North Carolina State University, which was established in 1887.

Polk also became active in the National Farmers’ Alliance, which had 100,000 members in North Carolina and had moved its headquarters there. He served as the Alliance’s president from 1889 to 1891. The Democratic Party showed little interest in the reforms he wanted, and he joined the new People’s Party (or Populist Party). Polk may well have become the party’s nominee for President in 1892, but he died suddenly that June.

The document below is an excerpt from a speech that Leonidas L. Polk gave before the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry in 1890, when he was president of the Farmers’ Alliance. In this speech, Polk provided a great deal of data showing the decline in farmers’ wealth since the Civil War, argued that this decline was not the farmers’ fault, and asked the Senate to enact laws that would help farmers.

MR. CHAIRMAN and GENTLEMEN of the COMMITTEE:

A convention of representative farmers was held in the city of St. Louis, December 3, 1889. That body, known as the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, represented twenty-three States and a constituency approximating, at that time, fifteen hundred thousand voters. Since the convention of our fathers, which gave us our national Constitution, no body of men has assembled in this country who were more profoundly impressed with the gravity of the situation, or were actuated with higher motive or more patriotic purpose. After a calm, dispassionate and earnest investigation of the conditions and causes which have led to the wide-spread and alarming depression that has paralyzed the great agricultural interests of the country, they outlined what they conceived to be a measure of relief. They appointed a committee on national legislation, which, under their instructions, has formulated and presented to both houses of Congress, a bill embodying, as it believes, a safe, proper and just solution of the financial trouble which threatens the agricultural interests of the country with bankruptcy and ruin. I refer to Senate bill No. 2806 Senate bill no. 2806 sought to to establish agricultural depots for the accommodation of farmers and planters, as well as increase the amount of currency circulating, introduced into your body by Senator Vance, of North CarolinaZebulon Vance served as U.S. Senator from 1878 until his death in 1894..

As faithful representatives, you must be satisfied as to whether the conditions and necessities of the country are such as to justify or require legislation in this direction. And whatever may be your conclusions as to the particular method here presented, of one thing I feel assured, the spectacle -- unparalleled in all our history -- of fifteen hundred thousand farmers -- quiet, unobtrusive, law-loving, law-abiding, conservative farmers -- standing at the doors of Congress demanding relief, must, at least, command your respectful, patriotic, earnest and profound consideration....

Decline in agricultural values.

In 1850 the farmers of the United States owned 70 per cent. of the total wealth of the country. In 1860 they owned about one-half the wealth of the country. In 1880 they owned about one-third the wealth of the country. In 1889 they owned a fraction less than one-fourth of the wealth of the country....

From 1850 to 1860 agriculture led manufacturing in increased value of products 10 per cent. From 1870 to 1880 manufacturing led agriculture 27 per cent., showing a difference of 37 per cent in favor of the growth of manufacturing.

The exports of American labor products show equally disparaging and discouraging exhibits:

| A[g]riculture | Manufactures | |

|---|---|---|

| In 1881 | $730,394,943 | $89,219,380 |

| In 1888 | 500,840,086 | 130,300,087 |

An increase during these seven years in our exports of manufactures of 46 per cent., and a decrease in those years of agricultural products of 31 per cent.

Values of staple crops.

| In 1866 the wheat, corn, rye, barley, buckwheat, hay, oats, potatoes, cotton, and tobacco sold for | $2,007,462,231 |

| The same crops for the year 1884, eighteen years later, sold for | 2,043,500,481 |

Notwithstanding the cultivated acreage had nearly doubled, and farm hands had doubled, and agricultural implements and machinery had vastly improved, yet the crops named for the year 1884 sold for only thirty-six millions, or less than 2 per cent., more than they did for the year 1866....

Corn.

| Crop | Bushels | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1888 | 1,987,790,000 | $677,561,580 |

| 1889 | 2,112,892,000 | 597,918,820 |

So while the crop of 1889 exceeded that of 1888 by 125,102,000 bushels, yet it would have brought at point of export $79,642,760 less money.

- 1860 to 1870, average price per bushel 96 cents.

- 1870 to 1880, average price per bushel 63 cents.

- 1880 to 1887, average price per bushel 46 cents.

- Price to-day 37 cents.

So that the corn farmer to-day pays in the products of his labor over two and one-half times as much for a dollar as he did during the years of 1860 to 1870. Indeed, throughout the great corn belt of the North-west and West, it is claimed that he cannot sell it to-day at a price covering the cost of its production....

If a farmer had given a mortgage in 1870 for $1,000 he could have paid it with 1,052 bushels of corn, but if he has paid one half of it, the remaining $500, without interest, would now require 1,351 bushels of corn to pay it. He could have paid the $1,000 with 606 bushels of wheat in 1870, but if he owed $500 of the debt to-day it would require 593 bushels to pay it. He could have paid the $1,000 in 1870 with 10 bales, or 5,000 pounds of cotton, but if he owed $500 of it to-day it takes 10 bales, or 5,000 pounds of cotton. In other words, the farmer must pay his debts with the products of his labor, and he must work twice as hard, and give twice as much cotton, corn, or wheat to-day as was required in 1870 to pay the same debt. But we are told by those high in position that the law of supply and demand controls prices. That may have been true before the operations of this ancient law of trade were practically supplanted by the more imperious law of greed, as now enforced under the mandates of monopolistic combinations for the pillage of honest laborPolk is arguing that the law of supply and demand may once have controlled prices, but that is no longer does, because railroads are monopolies and can demand any price they wish. If only one railroad serves a farmer, and that farmer has no other means to get his goods to market, then that farmer will have to pay whatever price the railroad charges — or go out of business. This is why, today, monopolies in the United States are usually either regulated or not permitted..

But granting that the law of supply and demand is in full force and effect, there are two ways in which prices change under this law. Either a change in demand, supply remaining the same, or a change in supply, demand remaining the same. But I assert, and statistics will sustain the assertion, that there has been no change in the great staple products relatively to demand or to population to justify this great depreciation in prices; unquestionably the demand has not diminished. Where then has been the change? Has the weight of the dollar been increased? Has the area of our acre of land been curtailed that it should have fallen in value from 33 to 50 per cent.? Does not, a pound of beef weigh now 16 ounces? Do we not now measure our wheat or corn by the same measure? Does not the cotton farmer give now the same number of ounces to every pound? Has the change been made in the quantity or quality of the commodity, or has it been made in money, the measure of its value? This is the great question that the farmers of the country desire and expect this Congress to explain....

Wealth of the United States.

1850.

- Total value of taxed and untaxed property $13,500,000,000

- Assessed value of property 5,275,000,000

- Of which the farmers were assessed 4,500,000,000

1860.

- Total value of taxed and untaxed property $31,000,000,000

- Assessed value of property 12,000,000,000

- Of which the farmers were assessed 10,500,000,000

1870.

- Total value of taxed and untaxed property $30,000,000,000

- Assessed value of property 15,350,000,000

- Of which the farmers were assessed 12,500,000,000

1880.

- Total value of taxed and untaxed property $43,000,500,000

- Assessed value of property 17,000,000,000

- Of which the farmers were assessed 14,000,000,000

In 1850 the farmers of the United States owned 70 per cent. of the total wealth of the country and paid 85 per cent. of its taxes. In 1860 they owned half the wealth of the country and paid 87 per cent. of its taxes. In 1880 they owned only one-fourth of the wealth of the country. The increase in their farm values during the 20 years, from 1860 to 1880, had dropped from 101 per cent. to only 9 per cent., and yet in this desperately reduced and weakened condition they paid 80 per cent. of the taxes of the country.

Mr. Chairman, is the agricultural interest of the country depressed? And is it due to a want of energy, of industry and of economy on the part of the farmer? All over the country he has been told for years by a certain school of political economists that indolence, inattention to business and extravagance were the prime causes of his increasing poverty. But when he comes to the capitol of the nation venerable Senators and prominent Government officials inform him that his financial ruin has been wrought through his industry and the merciful providence of nature's God; that he is absolutely bowed to the earth under a crushing load of overproduction. Are either of his advisers correct?... Our exports of food products, under proper and just conditions, should be the true measure of our production. But is it so? The normal ration of flour, as established by our Government, and which has been kindly furnished me by the Secretary of War, is 1 1/8 pounds per day, or 410 pounds per year. Assuming that our population numbers 65,000,000, to give each a normal ration would require 26,650,000,000 pounds, whereas we produced last year (deducing 56,000,000 bushels for seed) only 17,282,400,000 pounds, a deficit of 7,267,600,001 pounds. But if our population had consumed 2 1/3 ounces per day per capita more than they did consume, nothing would have remained for export. Will any sane man doubt, with our millions of people in our crowded cities, in our towns, in our mines, and all over the land, in their hovels of poverty, who are existing in a state of semi-starvation, that we could have consumed this additional pittance? And if the ruinous decline in prices be due to overproduction, why should it not be confined to those commodities for which a surplus is claimed? Why should all departments of labor share this universal depression in prices? No, Mr. Chairman, it is not overproduction, but under-consumption. There can be no overproduction in a land where the cry for bread is heard.

But we are told that we should be content and happy that "a dollar will buy more to-day than ever before." Mr. Chairman, the American farmer stands a faithful and sorrowing witness of the truth of that declaration. No man living knows better than he the purchasing power of a dollar. He knows that its power has been so augmented that it now demands double the amount of his labor and the surrender of his profits to meet its unjust and cruel exactions. Indeed, so arbitrary and domineering has its power become, that it has forced upon the public mind the grave question, whether the citizen or the dollar is to be the sovereign in this country. But with all its power will it pay for the farmer more interest? Will it pay more on his mortgage? Will it pay more debt? Will it pay more taxes? Will it pay more physicians' and lawyers' fees? From all sections of this magnificent country comes the universal wail of hard times and distress....

Mr. Chairman, retrogression in American agriculture means national decline, national decay, and ultimate and inevitable ruin. The glory of our civilization cannot survive the neglect of our agriculture; the power and grandeur of this great country cannot survive the degradation of the Americam farmer.

Struggle, toil and suffer as he may, each recurring year has brought to him smaller reward for his labor, until to-day, surrounded by the most wonderful progress and development the world has ever witnessed, he is confronted and appalled with impending bankruptcy and ruin. Crops may fail, disaster may come and sweep away his earnings as by a breath, prices may go below the cost of production, but the inevitable tax-collector never fails to call upon him with increased demands. Is it any wonder that these struggling and oppressed millions are organizing for relief and protection?

The causes.

We protest, with all reverence, that it is not God's fault. We protest that it is not the farmers' fault. We believe, and so charge, solemnly and deliberately, that it is the fault of the financial system of the Government -- a system that has placed on agriculture an undue, unjust, and intolerable proportion of the burthens of taxation, while it makes that great interest the helpless victim of the rapacious greed and tyrannical power of gold. A system through which, despite the admonitions of history and the experience of all countries in all ages; despite the teachings and warnings of the ablest men in the science of political economy in this and in all countries, our currency has been contracted to a volume totally inadequate to the necessities of the people and the demands of trade, and with the natural and inevitable result -- high priced money and low-priced products.

The remedy.

- Restore to silver its dignity and place as a money metal, with all the rights of coinage and all the qualities of legal tender which gold possesses.

- Issue sufficient amounts of currency direct to the people, at a low rate of interest, to meet the legitimate demands of the business of the country, and which shall be legal tender for all debts, public and private.

- Secure to such issue equal dignity with the money metals by basing it on real, tangible, substantial values.

Primary Source Citation:

Polk, L.L. "Agricultural Depression: Its Causes -- the Remedy." Speech of L. L. Polk, President of the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, before the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, April 22, 1890. Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1890.

Published online by Documenting the American South. University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/polk90/menu.html