Many African Americans were eager to serve their country, to fight in the war against Spain, and to support the efforts of black rebels in Cuba to win independence. But they wanted to serve on their own terms -- as equals with white soldiers. In 1898, blacks in the U.S. Army were restricted to four all-black regiments, commanded by white officers and stationed in isolated forts in the West. Black volunteers for the war against Spain wanted to serve under black officers, and they refused to be limited to "the culinary department" -- that is, to cooking for white soldiers and doing other menial labor.

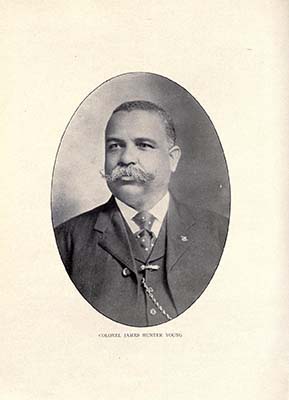

As in previous wars, the states were asked to organize regiments of volunteers. When President McKinley called for volunteers in April 1898, African Americans in Wilmington, New Bern, Raleigh, Charlotte, and Asheville quickly organized into companies and offered their services to Governor Daniel L. Russell. Russell had been elected governor in 1896 on a fusion ticket, supported by both Populists and Republicans and with nearly all of the black vote. Recognizing his debt to black voters, Russell agreed to create an all-black volunteer regiment. To command the regiment he commissioned James H. Young, the African American editor of the Raleigh Gazette and a former state representative who had been instrumental in founding a state school for the deaf, dumb, and blind.

North Carolina was one of only three states to create an all-black regiment commanded by black officers. Across the U.S., the black press praised the state and its Third Regiment. But many whites in North Carolina were unhappy with it. In that fall's election campaign, the Democrats used the black regiment as evidence of "Negro domination" of the government.

The Third was first stationed at Fort Macon, on an island near the southern end of the Outer Banks. There they could train in isolation, but when the soldiers visited nearby towns, whites were horrified by the presence of armed black men and their demands for equal treatment. In the middle of August, a riot nearly broke out in Morehead City after a conflict between black soldiers and local whites.

In September the regiment was transferred to Camp Poland, near Knoxville, Tennessee, where they received even worse treatment. Soldiers in a white regiment from Georgia threw rocks at them during drill and occasionally took shots at them. But local whites were gradually won over by the volunteers' behavior when they visited Knoxville, and the President's Commision to Investigate the Conduct of the War with Spain specially commended the Third North Carolina.

By this time, though, the war was already over, and the black volunteers quickly lost interest in the idea of military service. They had signed up to fight, they said, not for garrison duty at home. News of the election in North Carolina and the race riot in Wilmington didn't help their morale. Neither did news that the regiment would be transferred to Camp Haskell near Macon, Georgia, where racism and discrimination were worse than at home. Whites in Macon deeply resented the presence of black troops and blamed them for increases in violence and crime, though government investigators found no evidence of any particular misbehavior. At least four North Carolina soldiers were killed by white civilians, all of whom were acquitted when they pled "justifiable homicide."

The Third North Carolina was finally sent home in February, 1899, and the soldiers mustered out. A black alderman in Raleigh, Edward A. Johnson, asked the General Assembly to give appropriate recognition to African Americans who had performed "their duty under the flag." But the new Democratic legislature instead passed a law barring blacks from the State Guard, the militia. Col. Young was rewarded by having his name removed from the cornerstone of the school he had helped found. White supremacy had returned to North Carolina in full force, and it was not the last time that black soldiers would return home to less than a hero's welcome. But although they had never left the country and failed to win equal treatment through their service, the Third North Carolina was a source of pride to African Americans throughout North Carolina.