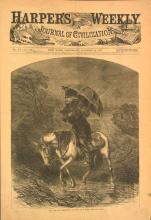

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, "circuit riders" preached to residents of the backcountry who were too scattered to be served by established churches.

John Wesley and his old friend George Whitefield were trying only to revive the Church of England (the Anglican Church) -- to spread its message to the working classes and the outcasts of England. Neither really meant to start a new denomination, only to update an old one. They wanted to save souls, to gather followers, to "beat the devil."

Whitefield was an itinerant preacher whose powerful style and presentation attracted large crowds wherever he went. Between 1739 and 1765, he visited North Carolina seven times. He preached about the love of God, the reality of sin, and the wonders of heaven. And his messages were remembered: sources say his sermons made "hell so vivid that one could find it on an atlas."

Not enough ministers, not enough need

After Wesley organized his followers into Methodist societies within the Church of England, official missionaries were assigned to the colonies. In 1772, Joseph Pilmore, another itinerant preacher, became the first official missionary to serve the North Carolina area.

Pilmore preached at Curritick Court House and then journeyed through the eastern portion of the colony. He visited Edenton, New Bern, Wilmington, and other locations where he found an audience. The conditions he found must have been disappointing. He found only eleven Anglican ministers in the entire colony. And in his journal, Pilmore called Edenton "a poor damp dirty place, where they have only preaching once in three weeks." He compared the people to "sheep having no Shepherd."

Even by 1790, twenty-nine out of every thirty North Carolinians did not belong to any church. Obviously, the harvest of souls would be ripe if a method could be found to reach the people and make them see their need.

Methodists make a move

The Methodist societies of the Church of England already had part of that method—an existing collection of itinerant preachers. By assigning these preachers to specific circuits in the colony, instead of letting them wander, they could spread Christian (and Methodist) beliefs to all parts of the North Carolina frontier. These circuit riding preachers would become known as circuit riders.

The first Methodist circuit to reach into North Carolina actually stretched into the Albemarle and down the coast from Virginia. But because of rapid and strong growth, a separate Carolina circuit was created in May 1776. That circuit was totally within North Carolina and was assigned to three circuit riders: Edward Dromgoole, Francis Poythress, and Isham Tatum.

Unfortunately, America’s War for Independence (1776-1783) had begun, and some Methodist preachers (who were really members of the Church of England, remember) went into hiding. When the war ended, many ties with England were broken. The tie between Wesley’s Methodist Society in America and the Church of England was broken as well, and the Methodist Episcopal Church was born in 1784. Francis Asbury was elected one of its first two bishops. The responsibility for assigning preachers to the many circuits fell completely to him and to other bishops who came after him.

Who were the circuit riders?

Circuit riders had to be young, in good health, and single (since marriage and a family forced preachers to settle in one area and leave the traveling ministry). Unlike their counterparts in other denominations, Methodist circuit riders did not have to have a formal education. Leaders of the new church wanted educated, trained circuit riders, but they wanted even more to spread their ministry to people on the frontier who needed Christian guidance.

Life was not easy for a circuit rider, partly because living conditions on the frontier were harsh. Enoch George, who later became a bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, said that serving the Pamlico Circuit in 1790 and 1791, he "was chilled by agues [malaria], burned by fevers, and, in sickness or health, beclouded by mosquitoes."

Circuit riders rarely served longer than one year in a circuit. Each year, they were appointed to a new area. This gave the preachers an opportunity to reuse their sermons and to perfect their delivery. It also kept them from growing too familiar with the local people and wanting to settle down.

The impact of circuit riders

Circuit riders had a simple plan of evangelism: They went where the people lived, and they ministered to their needs. Often, one of the first visitors to a family who had just arrived on the frontier was a Methodist circuit rider. During the day, he might help out with chores or assist with teaching the children. In the evening, after dinner, he would offer religious instruction to the family and to any neighbors who wished to join them.

If the preacher had found a warm welcome, he might spend the night with the family. Upon leaving the next day, he would usually promise to return the following month on a certain date to teach, preach, and hold services again.

These little pockets of people sometimes became the core of a new Methodist Episcopal congregation. As the community and population grew in size, church members often built a structure called a "brush arbor." Brush arbors were open shelters that had a flat top covered with brush for the roof.

These temporary shelters often served as a group’s first official place of worship. The host family for these new congregations (or sometimes the family that donated the land or materials for the brush arbor) frequently gave its name to the new place. Even today, many Methodist churches bear a family name such as Morris Chapel in Forsyth County or Cox’s Chapel in Randolph County.