We could say that all conflicts between European settlers in America and American Indians were about land. The Indians had it; the Europeans wanted it. In many cases, Europeans simply took what they wanted. In most of British North America, though, settlers actually purchased land from natives. You might think that buying land rather than taking it would prevent conflict. But because Europeans and American Indians had very different ideas about what it meant to buy and to "own" land, these deals actually could cause as much conflict as they prevented.

The traditional view of European-Indian land deals is that Europeans tricked the Indians, who failed to understand the consequences of their actions. In fact, though, Indians often proved savvy negotiators, and most European settlers understood far less about Indian ideas of land ownership than the Indians understood about theirs. In the long run, the colonists won nearly every conflict over land ownership, because there were more of them: Their numbers grew continually, while the native population dwindled from disease, warfare, and slavery.

But if force often settled land disputes, what caused them in the first place were vastly different assumptions about what it meant to "own" land -- assumptions deeply rooted in European and American Indian cultures and religions.

What is property?

Modern law recognizes two kinds of property: real property, which includes land and permanent structures built on it; and personal property which is essentially anything that a person can pack up and move somewhere else. The distinction between owning land and owning things is an important one, and the different ways in which American Indians and European settlers interpreted it helps to explain the conflicts that arose between them. Essentially, where Europeans saw land as private property, Indians saw it as the sum of its uses and a shared resource.

Land as a shared resource

At the simplest level of personal property, American Indians owned what they made with their own two hands. But unlike Europeans, they did not accumulate goods, and they freely shared tools and other useful possessions with friends and family who needed them.1 Other goods, such as beads and trinkets, might serve as displays of a person's rank or prowess, but they too were frequently traded or given away. While Indians had a definite concept of personal property, then, they tended not to be as "possessive" about their possessions as Europeans.

Land rights were more complicated. A family might "own" the land on which its house stood, and women "owned" the land they farmed. But homes, agricultural fields, and villages moved frequently, and so land was only "owned" as long as it was being used.

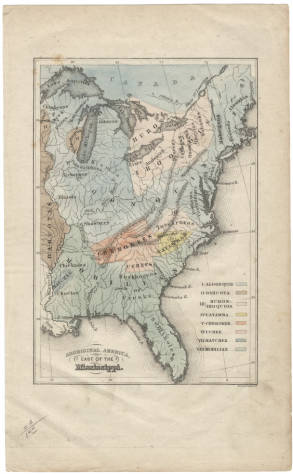

Villages collectively had rights to large territories that they used for hunting, fishing, and gathering of food, medicinal herbs, and raw materials for building or tools. Those rights shifted depending on the use and the people using it. For most purposes, all of the people in a village shared the use of its land. Among different villages, agreements about land use had to be made or defended. A village might claim exclusive hunting rights in a given territory, for example, but people from many villages might share the use of a single river for fishing. What villages claimed was, as historian William Cronon writes, "not the land but the things that were on the land during the various seasons of the year."2

Land as property

European ideas about land and property differed from those of Indians in two important ways. First, under European law, land was a commodity that could be bought and sold, and individuals who "owned" a tract of land had, for the most part, exclusive rights to its use. Second, ownership was determined by formal means, recognized by deeds and contracts and enforced by courts of law. Faced with the casual, shifting, and complex arrangements of America's native peoples, Europeans took several approaches to obtaining land.

Of course, King Charles II initially granted the entire territory of "Carolana" to the eight Lords Proprietors, who were then free to dispense with it as they saw fit. Prior to that, Amadas and Barlowe had claimed the Outer Banks in the name of Queen Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh. The English justified those claims, first, on the grounds that Charles, being a Christian monarch, had authority over a continent of heathen peoples.

They also argued, more specifically, that the Indians had failed to heed God's command in Genesis to "subdue" the land. In Europe, hunting was the sport of the wealthy, not a key source of food, and so to the European eye, the vast hunting grounds on which the Indians relied appeared uninhabited and "unimproved." The Indians, in other words, weren't using the land; therefore it was up for grabs.

Interestingly, despite these arguments, the English frequently purchased land from Indians rather than seizing it outright, and colonial law recognized Indian ownership of land. But the land deals and the courts that enforced them worked by European standards of land ownership that the Indians didn't share.

When they purchased land from Indians, Europeans understood the deal as a full transfer of rights. A man who purchased a tract of land was understood to have the right to use it for any purpose, sell it to whom he wished, and to forbid trespassers. Indians, by contrast, did not typically see themselves as signing away all rights to land. They may, for example, have understood a land sale to mean that the colonists could live on land in a native village's territory, but that all would continue to share hunting rights.

Conflicts

These philosophical differences turned into practical problems when Europeans bought land from Indians and when they clashed over who could use land to which both sides believed they had a right.

If nobody owns it, who gets to sell it?

Colonists wanting to buy land from Indians first had to figure out who owned it. That, as we've seen, was a tricky question to answer -- if not an impossible one. Europeans used to monarchy often assumed wrongly that the chief of a village could sell land on behalf of his people, when in fact his powers were far more limited. Europeans also assumed that every piece of land must either have a single owner or ruler or else be unowned, when in fact most land in America was shared in various ways.

As a result, colonists often paid for land only to find that other Indians did not recognize the sale. The colonists, though, maintained their claims, and colonials courts -- being established and run by the colonists themselves -- nearly always supported colonial interests in land disputes.

Managing land for hunting and farming

English colonists rarely, if ever, forcibly displaced an Indian village or took land currently being used for agriculture. In fact, in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, some colonists encouraged Indians to convert to Christianity, and farm for a living in permanent settlements, and welcomed those who did. Conflicts typically arose when Europeans wanted to settle and farm land on which Indians hunted or that they reserved for future agricultural use. Precisely this kind of misunderstanding may have sparked the Tuscarora War; the colonists at New Bern settled too close to the Tuscarora's best hunting and agricultural land.

Conflicts also arose over the way Indians managed their hunting grounds. Although Europeans saw Indian hunting grounds as unimproved, in fact, native peoples managed the land they used for hunting, often by setting fires to flush game and keep underbrush down. Indians continued to set fires before their hunts after Europeans arrived -- and often did so near European farms and settlements, on land to which they believed they retained hunting rights. Few colonists understood this practice, and seeing Indians setting fires near their homes frightened and angered them.

Letting livestock roam

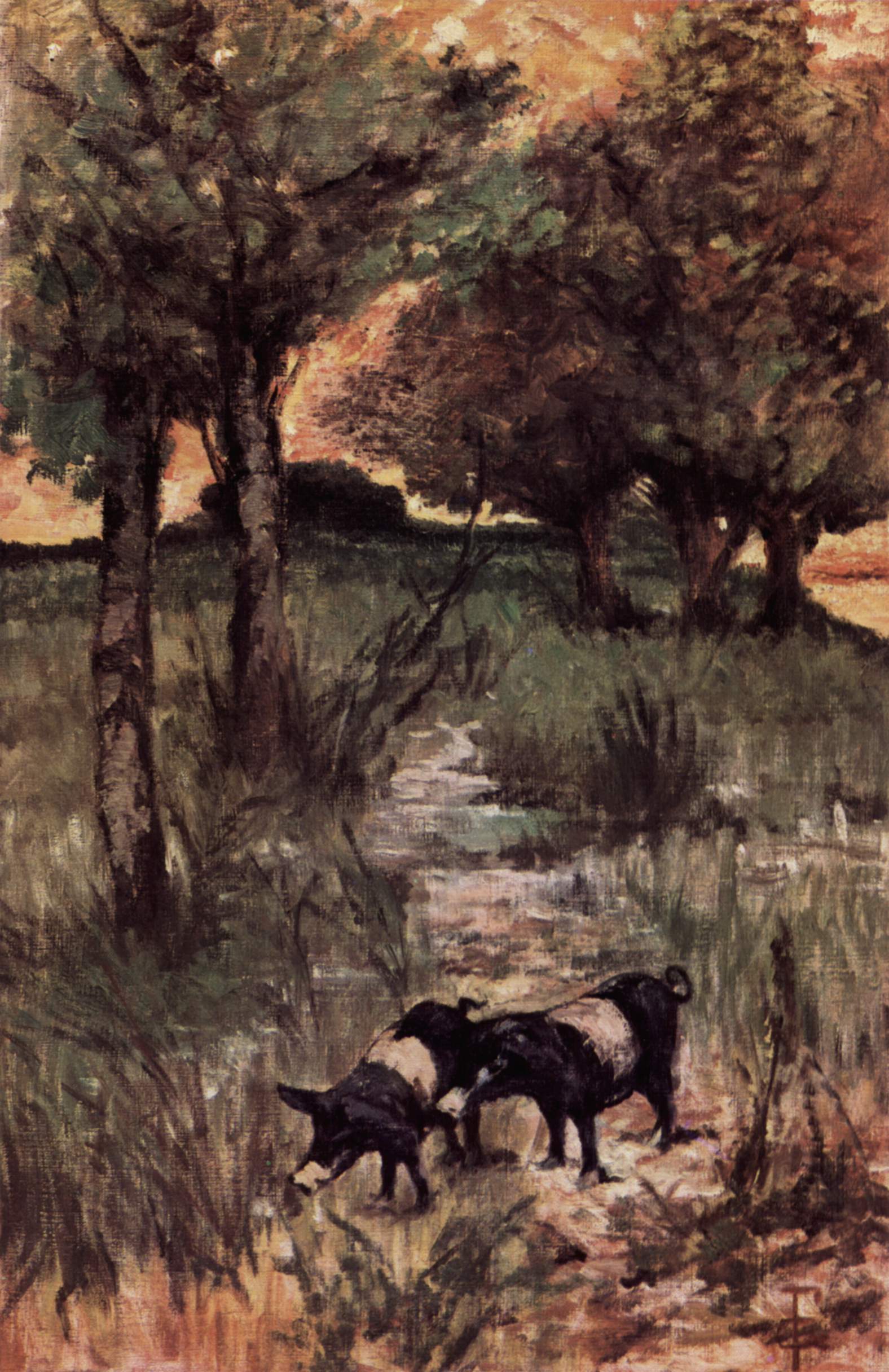

The question of whether natural resources could be privately owned applied not only to land, but to animals. Colonists allowed livestock such as pigs to roam freely, then rounded them up in fall and winter months for slaughter. By 1700 in England, laws required farmers to keep their livestock securely penned so that they wouldn't damage crops. But in North Carolina -- and throughout the South until the late 1800s -- the opposite was true. Livestock could range freely, and it was a farmer's responsibility to fence in his crops and to fence out other people's animals!3

In America in the 1600s and 1700s, there was so much open land -- and so many new farms without fences -- that the English rule of fencing in livestock never needed to take hold. By 1632, the Virginia legislature had to pass a law officially making it farmers' responsibility to fence in their crops "or else to plant upon their own peril." Virginia farmers seem to have brought the practice of freely ranging their livestock with them when they moved south into North Carolina later in the 1600s.

Allowing hogs and other livestock to roam freely benefited small farmers who might not otherwise have access to woods and streams. It also meant that farmers did not have to supplement their animals' feed -- pigs, in particular, could find all the food they needed in the woods. And since pigs are fairly dirty, letting them roam the woods rather than keeping them penned together near a dwelling probably kept disease down. But domestic animals would also have had a tremendous impact on North Carolina's woodlands. By trampling and rooting up undergrowth and eating new shoots of grasses and other plants, livestock transformed native ecosystems, contributed to soil erosion, and destroyed the habitats and food sources of native animals.

Indians, who did not raise animals for food and treated wild animals as a shared natural resource, did not always recognize Europeans' ownership of wandering livestock. Some Indians who gave or sold land to European settlers believed that they retained hunting rights to that land -- rights that, since they relied on hunting for food, were critical to their survival.4 Settlers frequently complained that Indians stole cattle and hogs that the Indians saw as theirs to take.

In the end, European ideas of land ownership -- backed by superior numbers, force of arms, and a relentless legal system -- won out. The colonists, as they believed their God commanded, subdued the land. But by parceling out and fencing off the land, they made native ways of life impossible. Indians who at first had warily accepted the strangers in their land slowly came to realize that coexistence would not be possible. The Tuscarora and their allies, diminished by disease and facing an insatiable colonial appetite for land, seem to have seen this coming in 1711, and the war they fought against North Carolina's colonists was a desperate stand for their existence.

- 1. Cronon, William, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of Colonial New England, rev. ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003), 61.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Free-ranging livestock remained standard practice in North Carolina until after the Civil War, and the state did not allow local governments to put the burden of fencing on the livestock owner until 1917. The last open livestock ranges in North Carolina were on the Outer Banks, and were not closed until the late 1950s. [For more about fencing laws, see "Fences" in the Encyclopedia of North Carolina, ed. William Powell (Chapel Hill, N.C.: UNC Press, 2006), pp. 424–425; and J. Crawford King, Jr., "The Closing of the Southern Range: An Exploratory Study," in The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Feb. 1982), pp. 53–70.]

- 4. See Joshua Piker, Okfuskee: A Creek Indian Town in Colonial America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 99.